Visual Learning Mythbusters

/You find this questionable statistic all over the dang place:

83% of people are visual learners.

From Stanley Kubrik's A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Sometimes it appears as 65% or some other percentage. Yet rarely — if ever— is that number attributed to any clinical research.

Our friends at ImageThink point towards a likely source of this idea.

Research conducted by Richard Felder resulted in a standardized test called the Index of Learning Styles (ILS) which sorts learners according to several different spectra, including visual-verbal.

And who doesn't love themselves a standardized test?

But that research was done well before fMRIs became available to measure brain activity and produce activation maps showing which parts of the brain are involved in a particular mental process.

(Felder's research was done primarily with — gasp! — engineering students.)

Unlike standardized tests, fMRIs work by detecting the changes in blood oxygenation and flow that occur in response to neural activity. When a brain area is more active it consumes more oxygen and, to meet this increased demand, blood flow increases to the active area.

The resulting activation maps can show us how our brains biologically react to thoughts and external stimuli. And what have these images revealed? Learning is a whole brain activity and no matter what kind of learning activity we are engaged in, we are making movies in our mind.

Now, for me — a former art school student, professional image maker and chronic daydreamer — saying that 83% of people are visual learners is like declaring:

“Study finds that 83% of people think that legs make walking easier!”

Or this claim from our favorite fake news newspaper, The Onion: “Study finds High School students retain only one-third of obsolete curriculum over summer”

So, why then is the 83% stat slung about so freely?

The Peer Pressure to Produce Percentages

photo: The Uniform House of Dixie by Dystopos (Flickr Creative Commons)

A huge motivation may be our human need for social proof — also known as informational social influence — in order to validate an activity.

Social proof is a psychological phenomenon where people assume the actions of others in an attempt to reflect correct behavior for a given situation.

Simply put, people want to make sure the behavior is alright — whether that behavior is wearing leather pants to a wedding, sporting a bow tie and a mullet hairstyle (which I did briefly in the late 80s) or allowing someone to draw big pictures during the boss' big presentation.

Think about the social calculus of High School, but with strategic planning sessions, careers, and mortgages on the line.

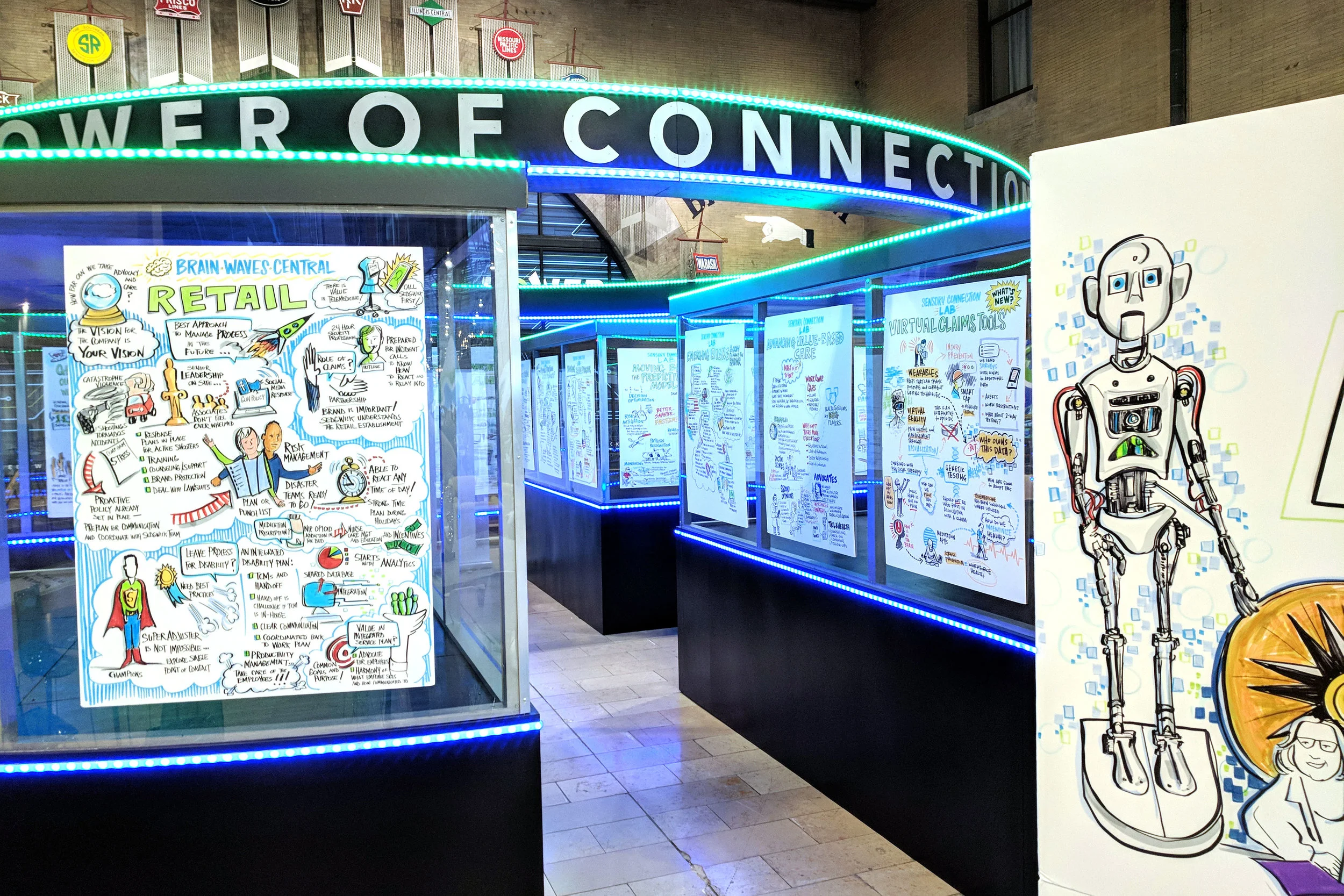

Ultimately, any professional who takes a chance to incorporate a new and artsy element, like graphic facilitation ( ! ), to a corporate event is taking a risk.

Granted, this particular risk (graphic facilitation) does not involve potential bodily harm or worldwide economic collapse.

No, this risk is of something much worse in the eyes of many — the fear of failing publicly.

More specifically, the fear may be of wasting time and treasure on something that does not yield concrete, quantifiable benefits.

Matthew McConaughey in his breakout role from Dazed and Confused (1993)

Hence, the affirmation that 83% of us need visuals to help us on our learning journey may be just the thing to make a jittery client feel alright, alright, alright!

Visual Learner, Schmisual Learner

photo: Stefan the Photofan (Flickr Creative Commons)

In a 2013 article in Scientific American, Sophie Guter asks if teaching to the student's style is bogus.

This may be anathema in a world of user-centered design and student-centered learning environments, but from her vantage point, she finds an educational landscape where many researchers suggest that differences in students’ learning styles may be as important as ability, but that empirical evidence is thin.

There is no shortage of ideas in the professional literature. David Kolb of Case Western Reserve University posits that personality divides learners into categories based on how actively or observationally they learn and whether they thrive on abstract concepts or concrete ones. Another conjecture holds that sequential learners understand information best when it is presented one step at a time whereas holistic learners benefit more from seeing the big picture. Psychologists have published at least 71 different hypotheses on learning styles.

Perhaps, this speaks less to learning styles — visual vs. kinesthetic vs. linguistic vs. mathematical — and more to this fact: any disengaged person ain't learning much.

A surefire way to engage learners of any age, is through consciously crafted stories and experiences that involve multiple senses and trigger multiple parts of our brains — without cognitive overload.

(Hello, Ritalin!)

Mythbusting Brains & Masters of the Mind

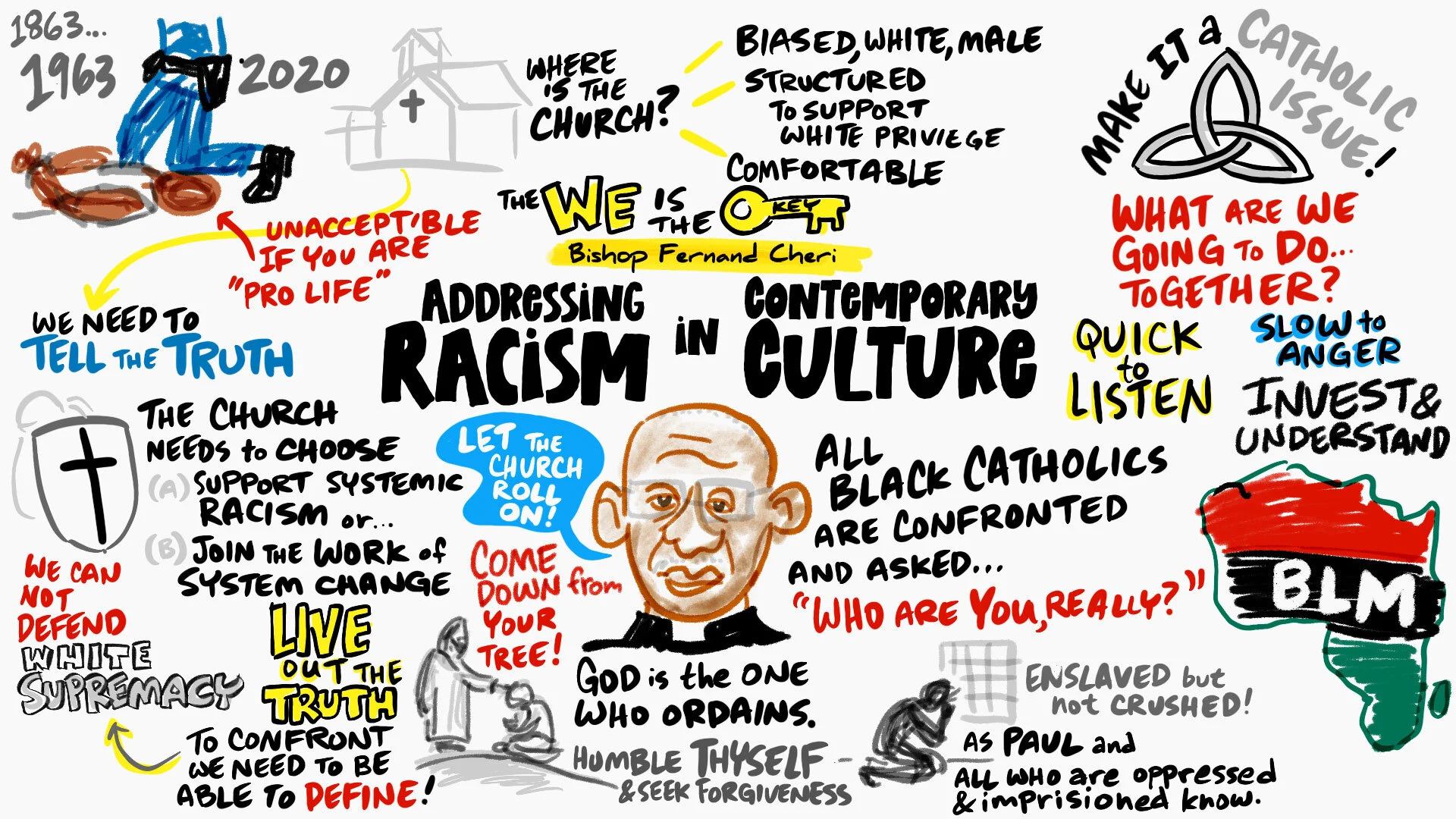

ABOVE: Illustration by one of my heroes, Dave Gray (source: Flickr, Creative Commons)

Because we are all visual learners — even blind folk, as you will learn by reading further down — I have collected some videos that have expanded my own horizons when it comes to understanding brains, visuals, and learning.

Below are several subject matter experts who explore the complexity of human neural networks to reveal rich constellations of biology, cognition, creativity and learning…

Antonio Damasio

“This rich film is continuously rolling in our minds.” Researchers like Antonio and his wife Hanna use imaging technology to explore the biological architecture influencing experiences that have traditionally remained the stuff of philosophy: The Mind, The Self, Consciousness and Culture. Like no one else, Damasio describes the biology that enables our memories and imagination.

What I Learned: Our ability to visualize emanates from our physical bodies, through the oldest parts of our brain stem, and echoes throughout our cerebral cortex. Now, I cannot trust anything I think or feel after hearing Damasio describe consciousness.

http://www.ted.com/talks/antonio_damasio_the_quest_to_understand_consciousness

David Eagleman

“Are we free to choose how we act? Is the mind equal to the brain?” A neuroscientist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Eagleman's research includes time perception, vision, synesthesia, and the intersection of neuroscience with the legal system. He is a pioneer on the power of the unconscious brain.

What I Learned: I asked David where dreams come from. He answered that dreaming is our brains natural function; it uses the body to check if the dream is reality!

Daniel Kish

“They call me the real life batman. My claim to fame is that I click.” World Access for the Blind, founded by Kish, trains the visually impaired to achieve greater freedom and mobility through echolocation — a technique that simulates a bat’s night vision of perceiving the environment through sound.

What I Learned: Kish taught me that unless severely damaged, all humans, regardless of visual ability, rely heavily on the visual cortex to navigate and shape their world.

Scott Barry Kaufman

“Depending on what you are creating, the stimulus, the content and what stage of the creative process you are in, different brain areas are recruited to help solve the task.” Cognitive psychologist by training, Kaufman unravels some of creativity’s mysterious origins with the help of brain scanning equipment. Kaufman's blog on the Scientific American website, Beautiful Minds, shares Insights into intelligence, creativity, and the mind.

What I Learned: The Left-Brain vs. Right-Brain debate is a farce: we are all whole-brained people, yet the phenomenon of “talent” and ”creativity” is vast and mysterious.

http://poptech.org/popcasts/scott_barry_kaufman_creative_brains

Pawan Sinha

“Being a blind kid in India is tremendously tough.” Sinha's humanitarian and scientific work sheds light on how the brain's visual system develops. Sinha and his team provide free vision-restoring treatment to children born blind, and then study how their brains learn to interpret visual data. The work offers insights into neuroscience, engineering and even autism.

What I Learned: The brain (not the eye) is what integrates all the different visual elements we see into objects we can understand; the one thing that the visual system needs in order to parse the world is motion.

http://www.ted.com/talks/pawan_sinha_on_how_brains_learn_to_see

Duygu Kuzum

“Have you ever seen the super computer, Watson? It is bigger than my apartment.” Kuzum develops nanoelectronic synaptic devices which emulate synaptic computation in the human brain, then works to interface these synapses with biological neurons. Such nanoscale synaptic devices have the potential to lead to interactive brain-inspired computer systems that can learn and process information in real time, bridging the gap between the human brain and digital computers.

What I Learned: The brain is so freaking efficient for the amount of processing it can do! Powered by less energy it takes to light a lightbulb, the human brain is really tough to replicate mechanically—or digitally!

Miriah Meyer

“We need to move beyond the idea that data visualization is about pretty pictures, and instead embrace that it is a deep investigation into sense-making.” Meyer explains how data visualization can be more concise, practical and scientifically useful, and still be aesthetically pleasing.

What I Learned: Good data graphics can accelerate the progress of scientific research—not simply serve as a nice illustration of that research.

http://www.alphachimp.com/poptech-art/miriah-meyer-seeing-data

Sunni Brown

“Doodling can have a profound impact on how we process information and how we solve problems." Studies show that sketching and doodling improve our comprehension — and our creative thinking. So why do we still feel embarrassed when we're caught doodling in a meeting? Sunni Brown says: Doodlers, unite!

What I Learned: Doodling should be leveraged in situations in which information density is very high and the need for processing that information is very important. Learn more from Sunni's book The Doodle Revolution.

QUESTION FOR YOU: What has your research revealed about visual learning? Let us know in the comments below!