The Fogginess of It All

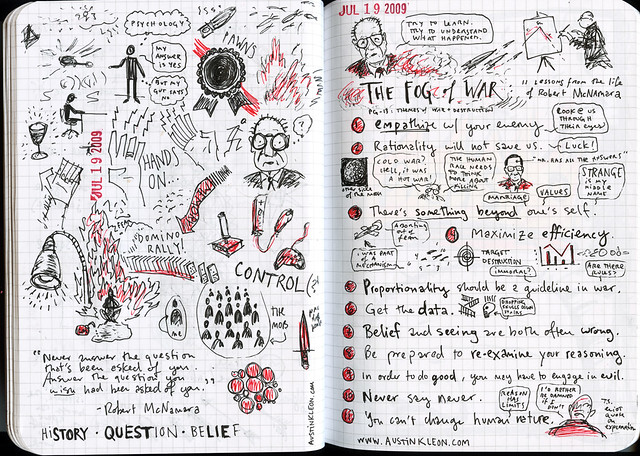

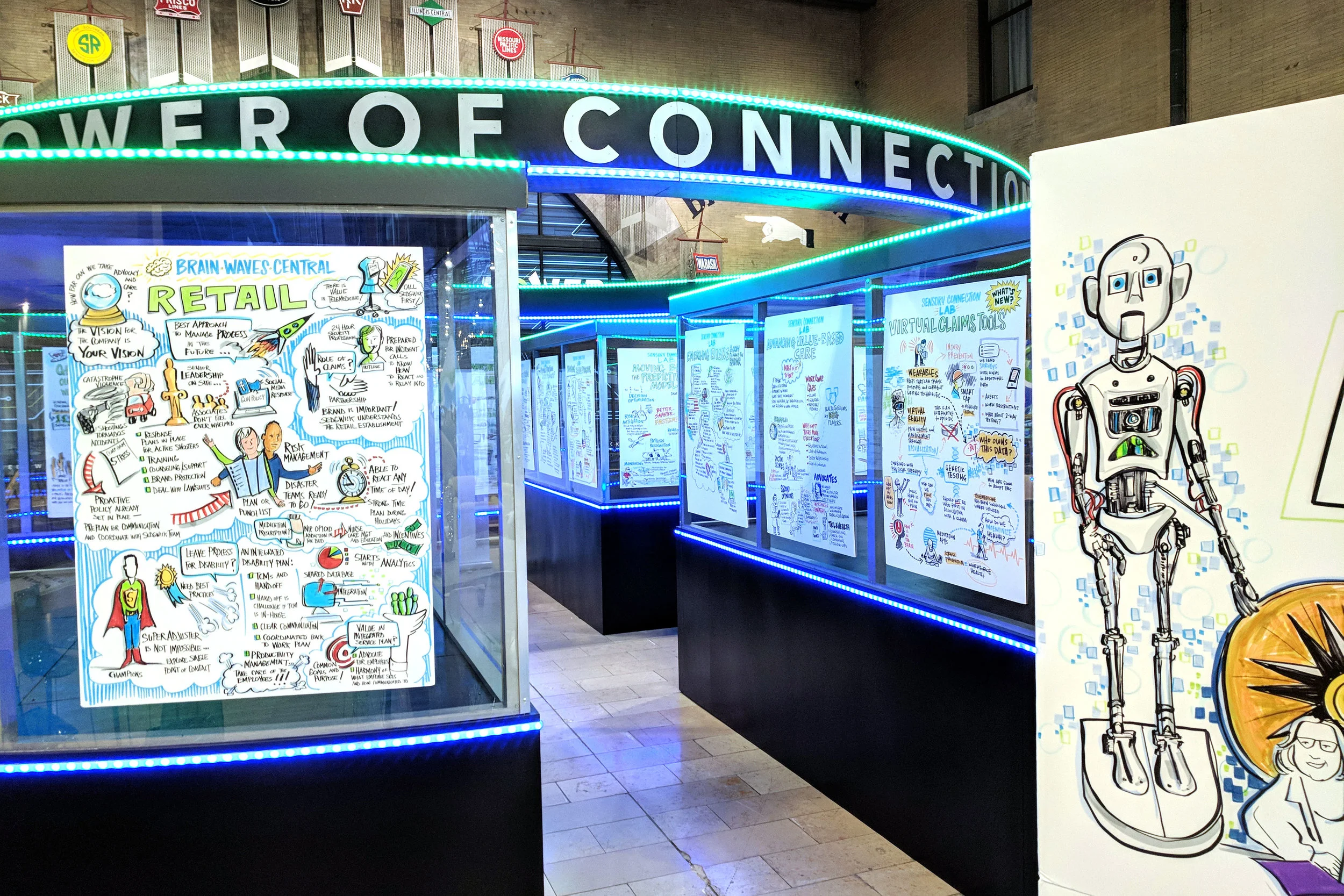

/ABOVE: Sketchnote by Austin Kleon who is awesome.

In 2003, filmmaker Errol Morris won the Academy Award for his feature length documentary, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara.

McNamara worked in the administrations of U.S. presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, serving 7 years as the Secretary of Defense through the Cuban Missile Crisis and the most brutal years of America’s war in Vietnam.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara at a news conference at the Pentagon in 1965. SOURCE: NY Times

Later in life, Robert McNamara went on to lead the World Bank, fight pandemics, lobby for economic development in impoverished countries, and build coalitions of governments to prevent nuclear proliferation.

But it was the Vietnam War that defined McNamara's legacy as this obituary from the NY Times aptly describes upon his death in 2009 at age 93:

The war became his personal nightmare. Nothing he did, none of the tools at his command — the power of American weapons, the forces of technology and logic, or the strength of American soldiers — could stop the armies of North Vietnam and their South Vietnamese allies, the Vietcong. He concluded well before leaving the Pentagon that the war was futile, but he did not share that insight with the public until late in life.

The movie title is derived from the military concept of the “fog of war,” that slippery state of confusion in most conflicts, when gathering information, assessing the truth, making decisions, and predicting the results seem futile. Everything is in flux, fuzzy, ill-defined.

The subtitle of the film refers to 11 lessons that underpin the structure of McNamara’s thinking about waging war, making peace and human nature.

Although distilled from a lifetime of witnessing human conflict, McNamara’s axioms are particularly poignant at describing the messy middle of any complex system rife with wicked problems.

A “wicked problem" is used to describe a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize.

(Need examples? Turn on the news or read the headlines.)

It took me a while to learn that the “wicked” in wicked problem does not indicate evil. On the contrary, it indicates resilience—these issues seem eternally resistance to resolution due to complex interdependencies such as culture, energy, health, food, water, disease, population, politics, psychology.

The effort to solve one aspect of a wicked problem may reveal or create other problems—often many, many more problems, all with unforeseen consequences.

We respond in a way that, at the time, we believe to be logical based upon what we see before us, whether demonic despots or dry data.

The problem is, as McNamara articulates in one of his lessons:

“Belief and seeing are often both wrong.”

In all organizations—whether military or humanitarian, corporate or community-based—there is a fogginess.

The bigger the mission, the more people deployed, the more geographic locations, the messier the message, and the fuzzier the intel. The signal-to-noise ratio gets skewed heavily towards the noise.

Even in the logical worlds of mathematics and physics, there is an admission within quantum mechanics know as Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle.

Although it refers to particle physics, the principle is useful in understanding why it is so difficult to understand and anticipate the behavior of complex, adaptive systems.

In order to study the momentum and position of a fast-moving target, you have to slow it down to measure it, thus changing the dynamic.

Imagine trying to predict the score of World Cup final match by stopping all of the action in order to measure the soccer ball.

F.O.G. = Poor Decisions

In relationship counseling, F.O.G. often serves as an acronym for dysfunctional relationships based upon Fear, Obligation & Guilt.

Anxiety, uncertainty, indecision, doubt… these are natural parts of navigating a complex world. Yet we as individuals feel fear of the unknown consequences of our actions, obligation to do the right thing, and guilt for feeling those emotions of uncertainty.

If you are feeling foggy as an individual or an organization,

it's time to snap out of it!

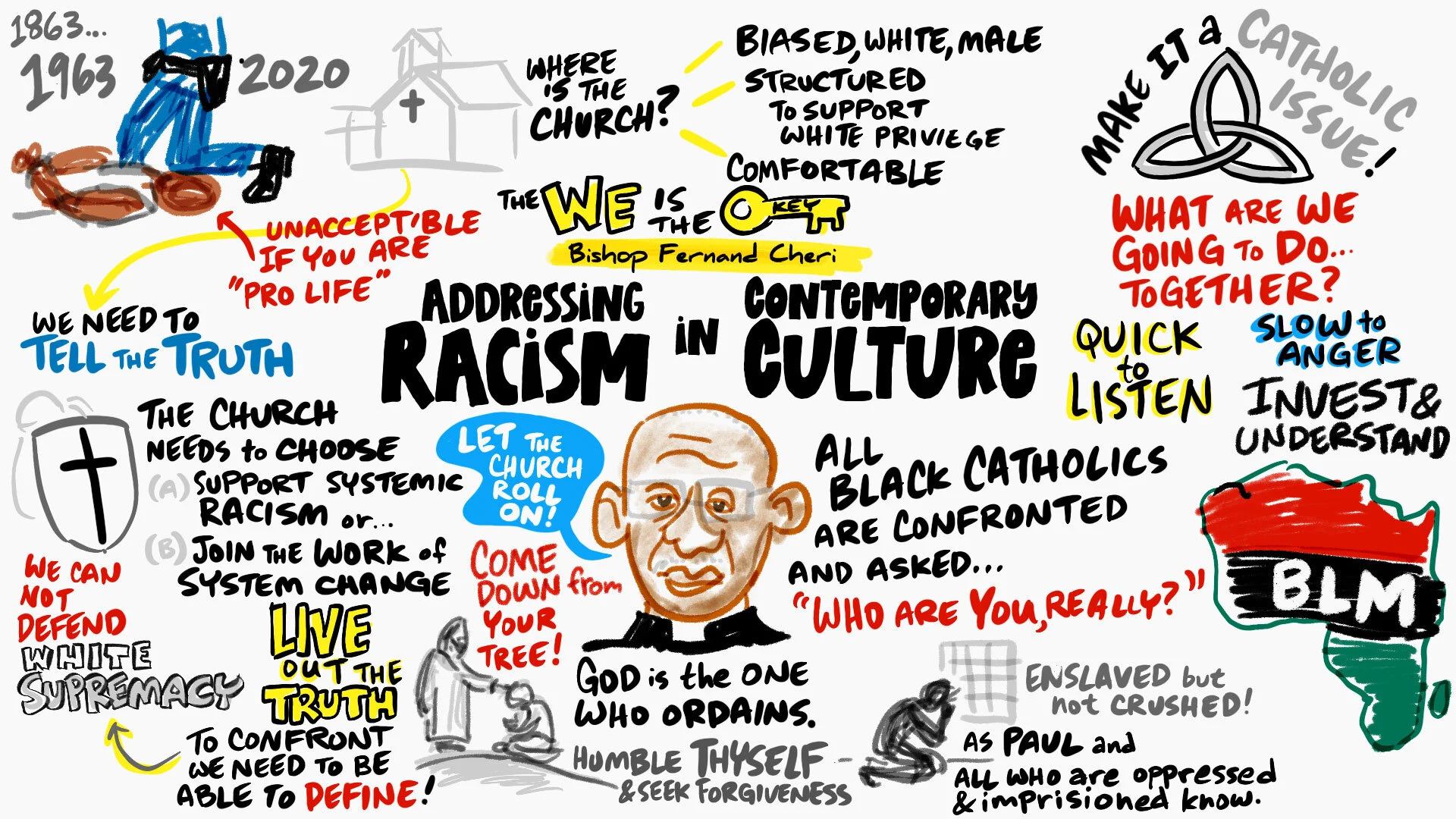

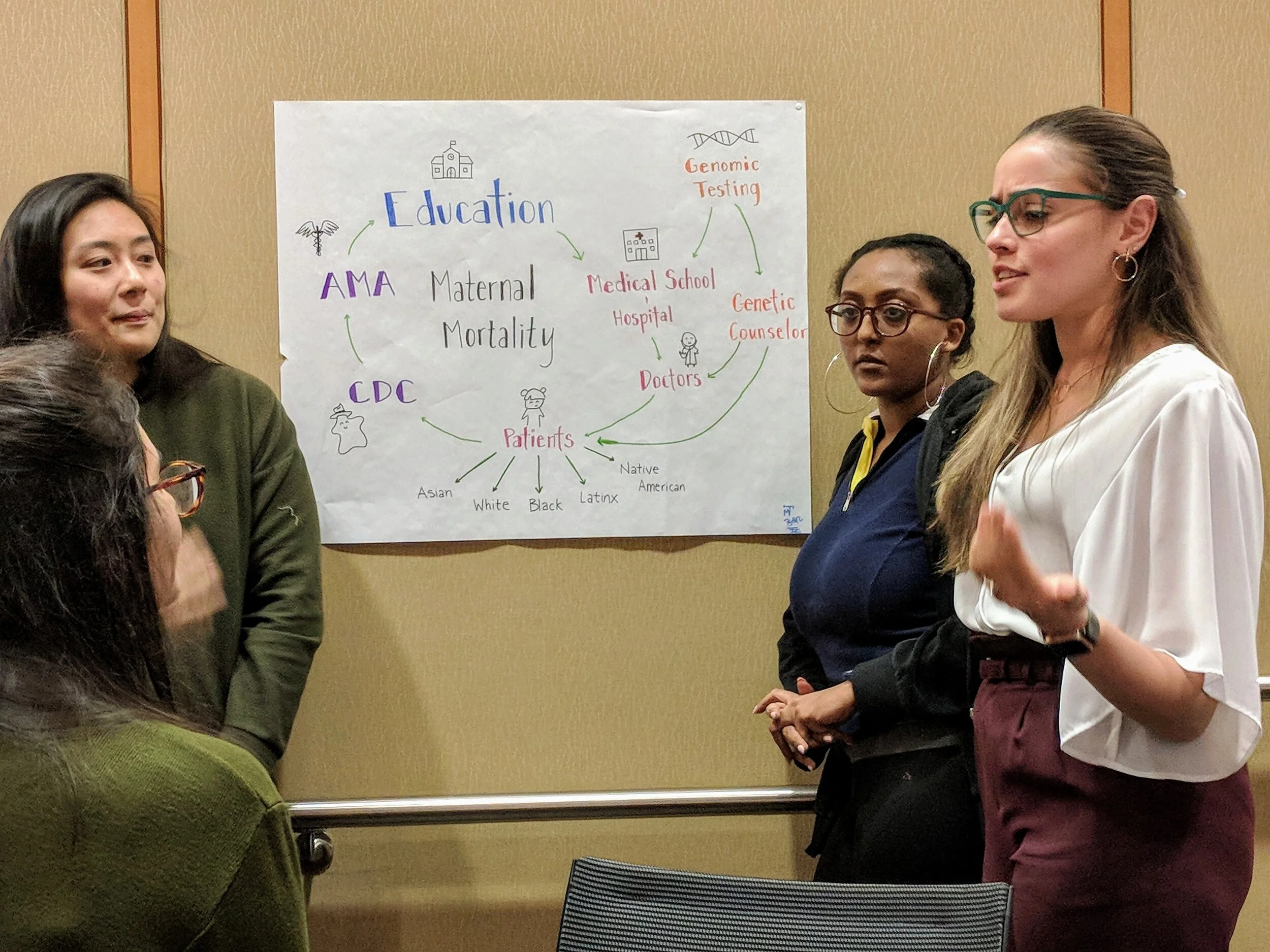

I promised that this post would (somehow) relate to graphic facilitation and visual learning, so here’s how:

It is my fundamental belief that the role of the visual facilitator is to help individuals and groups to:

- Better understand complex problems, so that they can…

- Make better decisions.

And my heartfelt hope is that this service activity can be a tool in alleviating human suffering.

(If you are still reading this, then you might be of the similar opinion.)

Whether your passion is working with kids who are aging out of the foster care system or building the next generation of driverless vehicles, visual facilitation and effective collaboration are powerful—and 100% necessary—tools for kicking ass and getting things done for the Greater Good.

But how does one overcome the fear of getting started with a new way of working... especially in settings where the stakes are high?

4 Lessons for Cutting Through The F.O.G.

This post is for those of you who are on the fence about making a decision—any decision—because you or someone close to you feels lost in the FOG.

LESSON 1 : Accept That There Is No Right Way

We all want a plan. We think there is a secret recipe… and there is!

In fact, there are thousands of secret recipes. However, the one that is going to work for you is the one that ends up working for you. As that patron saint of warriors and strategy consultants, Sun Tzu advises in The Art of War: “Use discipline to await the chaos of battle. Keep relaxed to await a crisis.”

Magnus Walker talks about his life journey of following his passion and going with his gut feeling which eventually led him to turning his dreams into his reality.

LESSON 2 : First Start, Then Steal

In his book, Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative, Austin Kleon (@austinkleon) describes the necessity of the act of stealing from those whom you admire: “If you copy from one author, it’s plagiarism, but if you copy from many, it’s research.”

Neil Williams (@neillyneil) is product lead for GOV.UK @gdsteam. In a post on Medium, Confessions of a First Time Sketchnoter, Williams details his journey from “guy who can't draw“ to a happy sketchnoter. He describes how he got started by copying two of his heroes, the aforementioned Austin Kleon and Mike Rohde.

Sketchnoting made me feel like a participant not a spectator, communicating with others who were favoriting, sharing and commenting on my notes and thanking me for them in person. I felt like part of the conference team, in direct contact with the speakers and organisers who were far more grateful for the notes than I dared imagine. And now I feel part of a movement — Mike Rohde’s Sketchnote Army — sharing my notes on Flickr groups and now writing this post.

LESSON 3 : Commit To The First Chunk

There is magic in starting something, anything!

When it comes to a new skill or activity, the magic happens in those first few hours.

Malcolm Gladwell (@InsideGladwell) never reports that one needs 10,000 hours of practice not to be good, not to be considered and expert, but to be a world phenomenon.

There is no guarantee, however, that practicing 10K hours will lead to such fame. Fortunately, author Josh Kaufman reveals that rapid skill acquisition only requires committing to the first 20 hours; in fact, 20 hours puts you on the path to learning anything.

LESSON 4 : Nobody Knows What The Hell They Are Doing

Around the time that puberty sets in, we begin to discover that adults don't really know what they are doing.

Even one of the most beloved, award-winning, dearly departed novelist, poet, and memoirist.

“I have written 11 books, but each time, I think ‘Uh-oh. They’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody and they’re going to find me out.’”

— Maya Angelou

Oliver Burkeman has a hunch about human psychology: our constant effort to eliminate the negative causes us to feel anxious, insecure, and unhappy.

Burkeman points out that the presenter on stage who’s giving a super-smooth presentation might well be a panicking wreck inside. “In fact, if he’s really good, he probably is panicking inside.”

In an article for 99U.com, he notes:

Research suggests that the so-called “impostor syndrome” may get worse as people get better: the more accomplished you get, the more likely you are to rub shoulders with ever more talented people, leaving you feeling even more inadequate by comparison.

In his book The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can't Stand Positive Thinking, Burkeman interviews therapists, scheisters, self-help hucksters, spiritual gurus, motivational speakers, religious practitioners and asks: “Why the hell are we so obsessed with pursuing happiness?”

Rise Above

I would like to end with a challenge to you, Dear Reader, to stagger through the fog, even if it's difficult, and use the tools of reflection and action to get above the haze.

While you are at it, experiment how you can use graphic facilitation and visual learning as a tool to cut through the fog. More on that in the next installment...